"History through The Korea Herald” revisits significant events and issues over the seven decades through articles, photos and editorial pieces published in the Herald and retell them from a contemporary perspective. – Ed.

This undated photo shows the inside of a chartered plane en route for the US carrying babies to be adopted by families there. (Ministry of the Interior and Safety)

When the dust from the 1950-53 Korean War settled, orphans were left to fight for survival. It was then a Christian couple from the US -- Harry and Bertha Holt -- stepped in to play a key role in arranging the babies to be adopted by foreign parents.

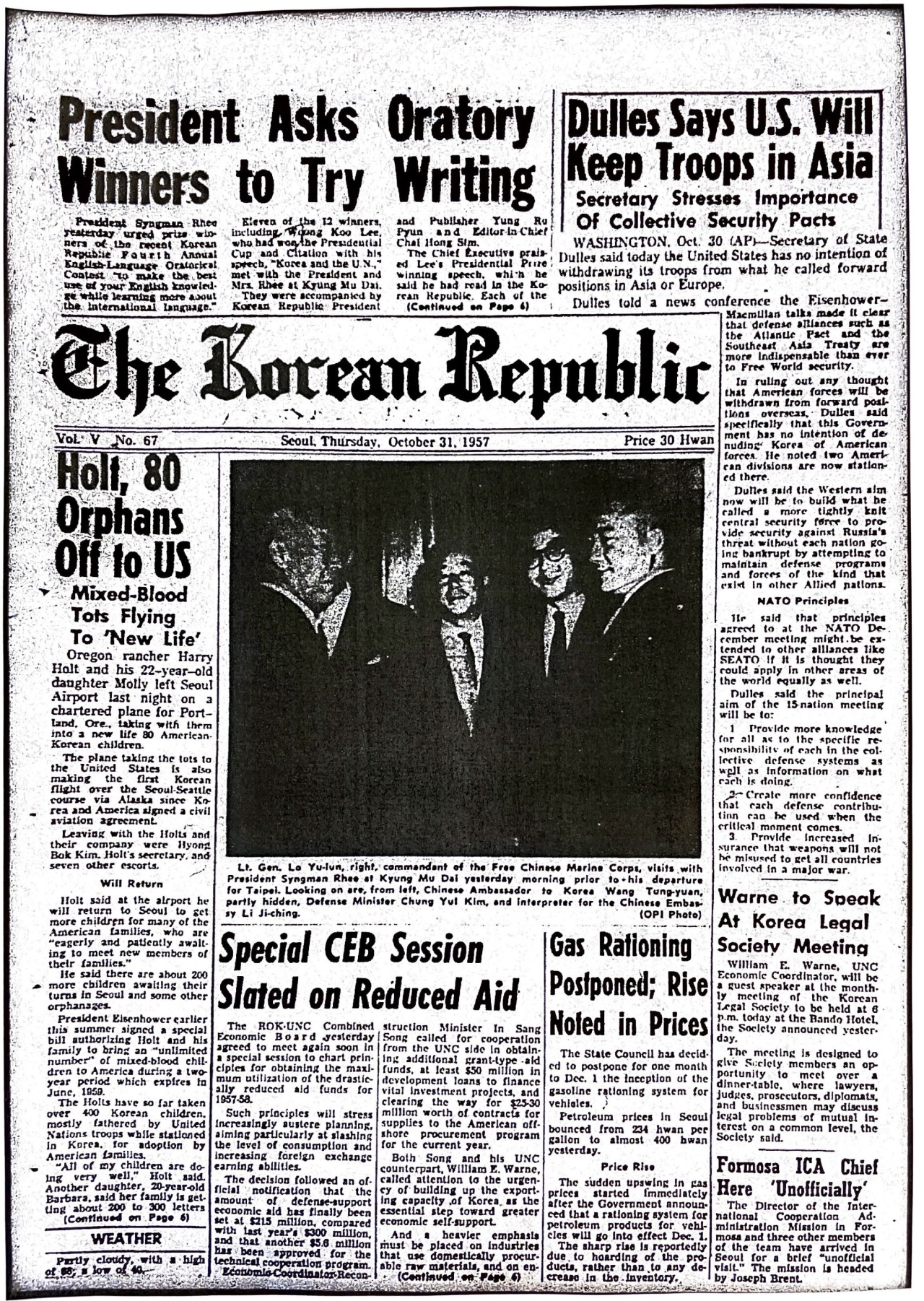

The Holts themselves adopted eight war orphans from Korea in 1955, and to help more, they established the Holt International Children's Services. The launch of the US-based humanitarian agency soon led to mass adoption of Korean war orphans -- especially mixed race children considered outcasts here -- by US parents, as shown on the front page of The Korea Herald, then called The Korean Republic, in its edition for Oct. 31, 1957.

Reflecting the optimistic mood surrounding the adoption project at the time, the article titled “Holt, 80 orphans off to US” said “Oregon rancher Harry Holt and his 22-year-old daughter Molly left Seoul Airport last night on a chartered plane for Portland, Oregon, taking with them into a new life 80 Korean-American children.”

“Holt said at the airport he will return to Seoul to get more children for many of the American families who are ‘eagerly and patiently awaiting to meet new members of their families,’” it added.

The article further explained that the Holts had taken over 400 Korean children as of October 1957. The orphaned children were “mostly fathered by United Nations troops while stationed in Korea.”

Over the years, the Holts’ initiative would eventually grow into a tidal wave of Korean infants, toddlers and children being flown out to foreign countries, with several other organizations participating as mediators.

The number of Koreans adopted in the US between 1955 to 1966 came to 6,293, according to the book “Culture, Ethnicity & Mental Illness” written by Albert C. Gaw, a clinical professor of psychiatry at University of California San Francisco. Of them, 46 percent are half Korean and half white, 41 percent are Korean, and the remaining are African Americans and Black Korean Americans.

In the '70s and '80s, even as the country started to pull itself out of poverty and write the “Miracle of the Han River” story, massive numbers of babies were still being given up for overseas adoption.

The number of children adopted overseas jumped sevenfold from 6,166 in the decade spanning the '60s to 46,035 in the '70s, according to data from Seoul’s Ministry of Health and Welfare. It peaked at 66,511 in the '80s, before falling to 22,925 in the '90s.

A total of 169,483 South Koreans were put to adoption to overseas parents from the beginning of 1953 to end-2021, latest data compiled by Statistics Korea showed.

Baby exports

Before K-pop and Samsung mobile phones, Korea’s main exports in the '80s were orphaned babies. At the time, not many Koreans saw problems with “sending babies “for a chance to get a new family.” After all, domestic adoptions only rarely took place.

The front page of the Oct. 31, 1957 edition of The Korean Republic, the forerunner of The Korea Herald.

Koreans’ collective indifference to the babies sent away was met with a real slap in the face in the 1980s, when international media began to highlight the “international adoption business,” with this Asian country as a central player in it.

At that time Korea was just beginning to be recognized globally, as one of the Four Asian Dragons and media coverage also zoomed in on the nation’s adoption practices and their ethical implications.

“This flow of children overseas began when South Korea was a poor nation, its cities and families devastated by the Korean War. That it continues now, when South Korea boasts skyscrapers, giant factories and the 1988 Olympic Games, is prompting questions,” a 1988 New York Times article titled “Babies for Export: And Now the Painful Questions” said.

The article highlights the business aspect of the adoption culture, pointing out that sending children overseas “spares the (Korean) government the expense of caring for them.”

The Korean government at the time licensed four adoption agencies to handle all the procedures, according to the article. The adoptive parents would pay some $4,000 for “transportation costs, medical expenses, payments to Korean foster parents and adoption agency processing costs.”

An unnamed adoption agency told the New York Times there is “virtually no charge” when Korean parents adopt Korean children, alluding that it was foreign adoptions that were keeping the agencies financially afloat.

The Progressive, a left-leaning magazine in the US, claimed in an article that the Korean government had made $15 million to $20 million annually from the “peculiar South Korean business.”

Alarmed of the global criticisms that came with the revelations, Korea began to cut back on its baby exports.

Adoptees demand answersNow all grown up, Korean adoptees demand explanations.

Adoptees claim their adoption process -- handled by Holt International and other adoption agencies -- were riddled with mistakes, misinformation and fabrications. They called on the government to launch a probe into them.

Last year, a group of Korean adoptees in Europe formally requested Seoul’s state reconciliation panel to look into past adoption cases, which they say were essentially human rights abuses.

Fifty-one members of the Danish Korean Rights Group -- comprising some 500 Korean adoptees in Denmark -- accused Holt of falsifying documents such as biological origins, birth names and parents to smoothen the adoption process, in the document filed with the Truth and Reconciliation Commission here.

“We realize that the adoption agencies here, Holt and Korea Social Service systematically falsified documents that made the adoptees seem like orphans on paper (despite their parents being alive at the time),” the document in Korean read.

“Though the adoption agencies were officially nonprofit we realize they accepted millions of dollars in the form of donations. We requested the commission to investigate how the money was used.”

The commission began the probe into the alleged human rights violations in December last year. Holt has yet to release a comment on the matter.

![[From the Scene] Monks, Buddhists hail return of remains of Buddhas](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=645&simg=/content/image/2024/04/19/20240419050617_0.jpg&u=20240419175937)