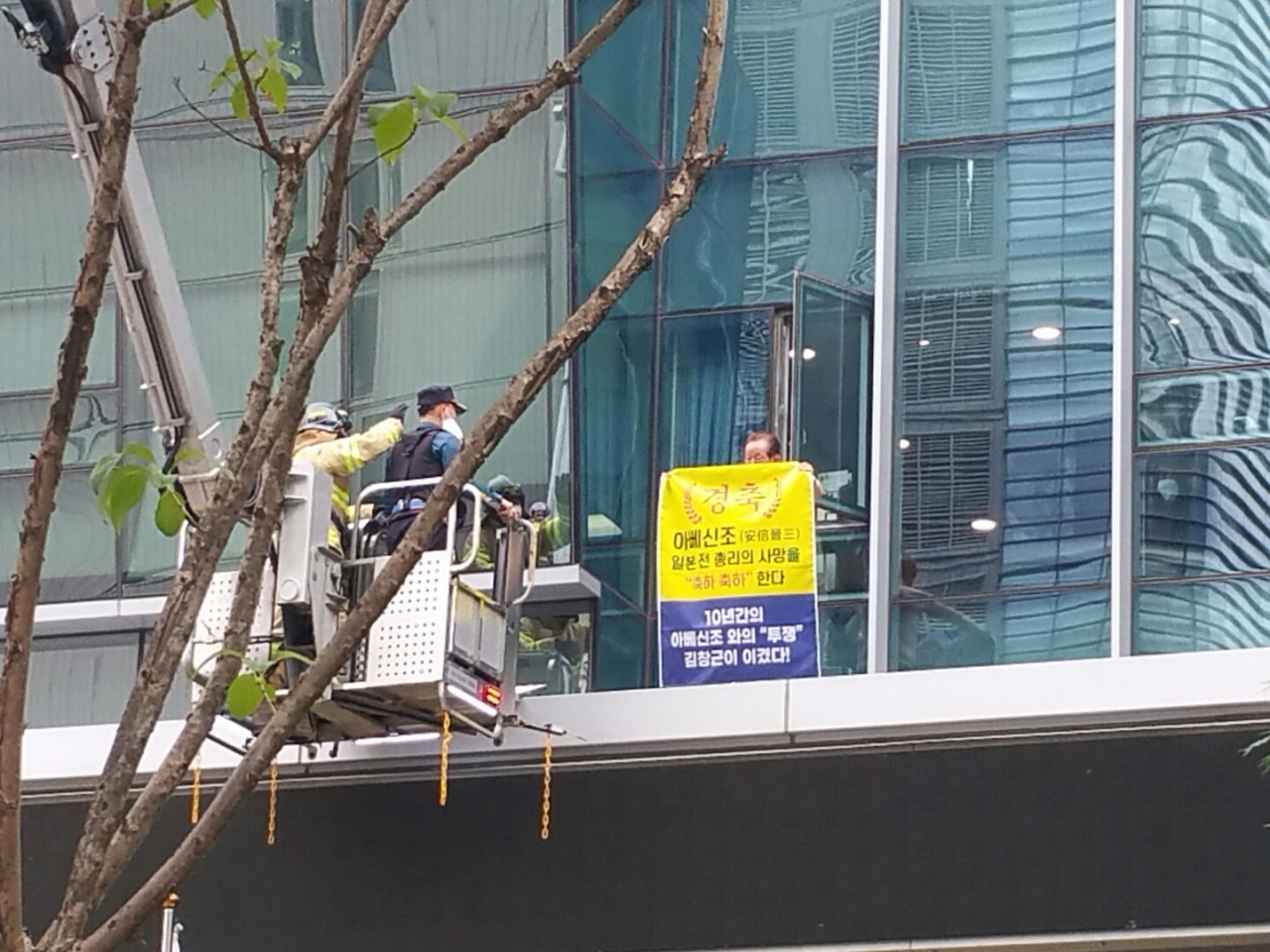

A half-naked elderly man stood precariously on a balcony of a high-rise building in Jongno-gu, central Seoul, hoisting a banner with an anti-Japan message.

A few meters away, a group of elderly women shouted insults at two dozen people taking part in a rally, locally referred to as "the Wednesday protests," demanding an official apology by Japan for the sexual enslavement of Korean women during World War II.

A few others standing nearby claimed the whole thing as a fraud. The women were voluntary prostitutes, not sex slaves, they argued.

This week again, chaos reigned on the street of Yulgok-ro-5 gil, where the 1,563rd Wednesday rally was held.

Clash of protests

It has been sometime already that the Wednesday rally, the world’s longest-running protest movement, has turned into a chaotic amalgam of conflicting voices on the issue of "comfort women" -- a euphemism for the women who were coerced into prostitution at the front-line brothels for Japanese soldiers.

The weekly demonstration began in 1992, organized by the Korean Council for Justice and Remembrance for the Issues of Military Sexual Slavery by Japan, in front of the former location of the Japanese Embassy in Seoul. The same group in 2011 erected the Statue of Peace, a human-sized sculpture symbolizing comfort women, in front of the building. In 2015, the Japanese Embassy moved to a new building nearby, but the rally has stayed where the statue stands.

Over the years, the movement for comfort women has received broad public support here, widely credited for bringing the issue to the attention of global citizens.

But in recent years, there have been growing voices questioning the integrity of the civic group Korea Council for Justice and the legitimacy of the comfort women's testimonies.

Across the street from the pro-comfort women protest on Wednesday was the group calling itself Coalition to Settle the Comfort Women Fraud, launched earlier this year.

The group claims that the comfort women were never forcibly mobilized by the Japanese government in the first place.

Lew Seok-choon, a former sociology professor of Yonsei University, controversially claimed that the women had chosen prostitution out of poverty. He has been indicted for defaming the victims in 2020.

“These women worked hard for a living, but the (comfort women groups) are using them for political purpose ... I didn’t defame these women, but defended them,” he said during a recent forum held by the group.

The anti-comfort women protests by the group consisted of a little more than a dozen people scattered across the area, with a microphone blasting the group’s claims mixed with profanity.

Another group at the venue took issue with the Peace Statue, viewing it as a hindrance to any progress in Korea-Japan relations. The statue is a mere representation of anti-Japan sentiment and should be demolished, they argued.

Protests by the far-right groups have expanded across the borders. In June, four members of the aforementioned Coalition to Settle the Comfort Women Fraud held a protest in front of the comfort women statue erected in Berlin two years ago. The council of Mitte borough, at which the statue stands, has adopted the resolution to permanently keep the statue.

Shooting the messenger

Before 2020, the mood was drastically different. There was no group planning a counter-rally in front of the Statue of Peace.

The attacks against the comfort women protests and criticism toward the Korean Council surged in 2020 around the time when Rep. Yoon Mee-hyang, a former leader of the group who won a parliamentary seat on the ticket of the liberal Democratic Party of Korea, was accused of embezzling funds related to the group. Yoon had been head of the group from 2008. One of the surviving victims, Lee Yong-soo, ignited the dispute by accusing Yoon of extorting her and her fellow former comfort women, in a public press conference held earlier in the year.

She claimed that the donations collected by the Korean Council had never been used for the victims, saying that the Wednesday demonstrations should be discontinued and that she will no longer take part in it. Yoon’s ongoing trial concerning the allegations has been delayed multiple times and has yet to yield a result, as of September.

Although Lee flip-flopped months after her accusations, vowing to work with the Korean Council again, the group’s integrity took a major hit in the public’s eyes.

The Korean Council was also criticized by a group of 33 former comfort women in a public statement back in 2004 for allegedly using them to collect funds. The criticism against the group rose again with the revelation that Korean Council excluded names of the former comfort women critical of the group in its memorial in Namsan, including Shim Mi-ja who participated in the aforementioned statement in 2004.

The victims’ bashing of the Korean Council was focused on alleged misuse of the donations and not the authenticity of the comfort women’s claims that they were sexually enslaved by the Japanese soldiers during the war.

But those participating in the anti-comfort women protests in Jongno on Wednesday all argued that such claims were lies meant to stir anti-Japan sentiments in the country.

Placards and banners hoisted at the scene bore words including “Stop distorting the history of comfort women and conscripted workers,” calling the statue “anti-Japan statue,” “Stop the comfort women fraud that waged on for 30 years,” “There is no future for the nation that lies,” and “demolish the comfort women statue.”

Despite the outspoken messages and loud volume, the protests were hardly populous in number. A solitary member of the Freedom Coalition stood in front of the loudspeaker that played prerecorded messages, and just seven people stood across the street from the Wednesday demonstrations, crying fraud to the 11 surviving former comfort women living in the country.

![[KH Explains] How should Korea adjust its trade defenses against Chinese EVs?](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=645&simg=/content/image/2024/04/15/20240415050562_0.jpg&u=20240415144419)